In Praise of Traditional Food Processing

Last Updated June 18, 2014 · First Published October 11, 2010

Cynthia Harriman is Director of Food and Nutrition Strategies for Oldways, the Boston-based non-profit best known for creation of the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid and the Whole Grain Stamp. For two decades, Oldways has crafted positive and practical programs to change the way people eat, with special emphasis on the benefits of the “old ways” of eating.

The group researches food traditions around the world, uncovers the science that explains the abiding success of these healthy traditions, then works with scientists, health professionals and consumers to support industry efforts to adapt the old ways to today. In this Guest Post, Cynthia reflects on healthy traditions for processing food.

If you just discovered October: Unprocessed, go here to find out more and take the pledge. Don’t worry if you missed the start date! You can start your 30 days today, or simply join in for the rest of the month.

I write to sing the praises of processed food, as my contribution to October: Unprocessed. Without food processed in traditional, healthy ways, mankind would have become extinct long ago.

Our existence today owes a lot to the fact that our distant ancestors learned how to take fresh milk, with its unrefrigerated shelf life of just a few hours, and process it into yogurt, or into cheeses that would last for weeks, months or even years. We learned how to take fresh cabbage and process it into sauerkraut (if we were German) or kimchi (if we were Korean), to provide vital vitamin C and other nutrients during the long winter months. We learned how to steam wheat and dry it on our rooftops to create bulgur, one of the first processed grain convenience foods (“Cooks in minutes!” I imagine the Babylon Bugle ad saying, in 2302 B.C.)

People have always processed food, to extend its shelf life beyond the harvest, to facilitate long-distance trade, and for better food safety. In fact, one of the common features of most traditional processing methods was this: they worked by encouraging the proliferation of good bacteria, which crowded out the dangerous bacteria that cause food to rot and that threaten our health and our lives.

Think back to the foods I mentioned earlier. Milk turns into yogurt when healthy Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria and other probiotics, traditionally from an earlier batch of yogurt, proliferate in the milk. When the milk is overflowing with good bacteria, the bad ones get squeezed out. Same thing with cheeses. Think of all those lovely blue cheeses and remember that they’re teeming with mold (yes, that’s the blue stuff) and bacteria. Traditional pickles, like sauerkraut and kimchi, are made with lacto-fermentation (a process of aging in a soup of various lactic acid bacteria).

In fact, these good bacteria not only protect us from the bad guys, but produce positive benefits in their own right. The probiotics in yogurt and lacto-fermented vegetables may help boost our immune system. Breads produced with long fermentation periods (sourdough breads) stay fresh longer than quick yeast breads, without the use of artificial additives.

Today, in an effort to make food predictably uniform, many of these traditional processes have been replaced with different approaches. Yogurt may be made with starches and gums and may have absolutely no live cultures. Cheese may be loaded with emulsifiers, extra whey, and preservatives and become processed cheese food. Pickles are made with vinegar instead of with lacto-fermentation. Breads use yeast and dough conditioners instead of traditional sourdoughs.

Living bacteria, even the friendly ones, are independent critters. It’s easier to make a dependably-crunchy pickle with vinegar than with lacto-fermentation, according to people who’ve done both. All of us who have baked sourdough bread know the heartache of seeing our starter die – or conversely, bubble over in the fridge, out of control – and even when everything goes right, the dough doesn’t rise exactly on schedule. It’s easier to use yeast and preservatives. Factories don’t have much patience with processes that aren’t precisely predictable.

On top of that, bacteria get such a bad rap. If you ask the average man or woman on the street whether they would prefer to eat food with or without bacteria, most people would say, “Ewww. Without bacteria.” In the public eye, the ideal food is sterile, inert, totally cleansed of anything living.

Trouble is, our ancestors evolved eating foods teeming with good bacteria, and our bodies may well depend on them to maintain a healthy balance of gut microflora. Today, when E. coli and Salmonella may be lurking in the food on your plate, it’s more important than ever to have an army of good bacteria inside you, waiting to fight off the bad guys.

With this in mind, maybe what we need to promote is a revival of the wisdom of traditional processing methods, adapted to the factories, food distribution systems, and families of the 21st century. It may already be happening, in fact. I noted a study from China just last month titled High Throughput Biotechnology in Traditional Fermented Food Industry that addressed just this subject, of how to adapt traditional fermented foods, with their increasingly-appreciated health benefits, to the factory environment.

Some smart companies are already making it happen. Last spring, I visited a really cool rye bread factory in Denmark, where the dough fermented for hours, and the finished bread was nothing more than whole, unground, rye berries held together with sourdough starter. It was the most seriously whole-grain bread I had ever eaten, and I savored every bite.

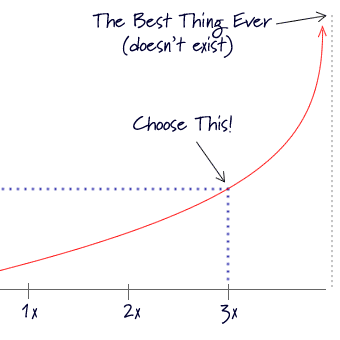

It’s not realistic to sit in the middle of a field or orchard and eat foods just as they come off the stalk or the branch. We all love the convenience of modern foods, but we want – and need – them with the health benefits and good taste of the old ways of food processing. The food companies that figure out how to offer us all of this, in one neat package, will have my food dollar, and, I suspect, that of many other people reading this blog.

Thank you Cynthia. You’ve given a new perspective on unprocessed. I would love to know your views on fermentation and soy products. I have been told by two well-studied nutritionists that certain soy products should be avoided or reduced.

Glad you liked the post, Nance. I personally tend to eat foods that have been around awhile, on the basic premise that our bodies evolved eating such foods. There are so many delicious whole foods around that I can eat a wonderfully, diverse diet without taking a chance on making my body into a chemical experiment for new processes or additives. I don’t do a lot of soy – it’s just not a favorite – but when I do, I eat both fermented soy products (like tamari, miso, tempeh) and non-fermented soy products (soy milk, tofu), just as I eat both fermented and unfermented grains and dairy – they’re all whole food forms in my view. I avoid soy that isn’t labeled organic (it’s almost certainly GMO) and stuff like soy isolates and hydrolyzed soy protein. The main reason many people feel strongly about sprouting, soaking, or fermenting foods like… Read more »

Agreed! Great post. And you’ve reminded me that I still wish to try my hand at sauerkraut…

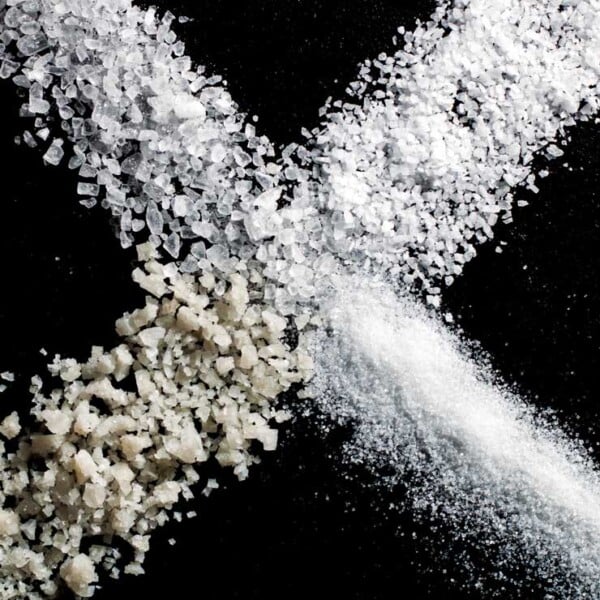

Alta – I’ve been wanting to try Sauerkraut at home, too. From what I hear, all you really need are a crock pot, some finely-shredded cabbage, and salt… Let us know how it goes!